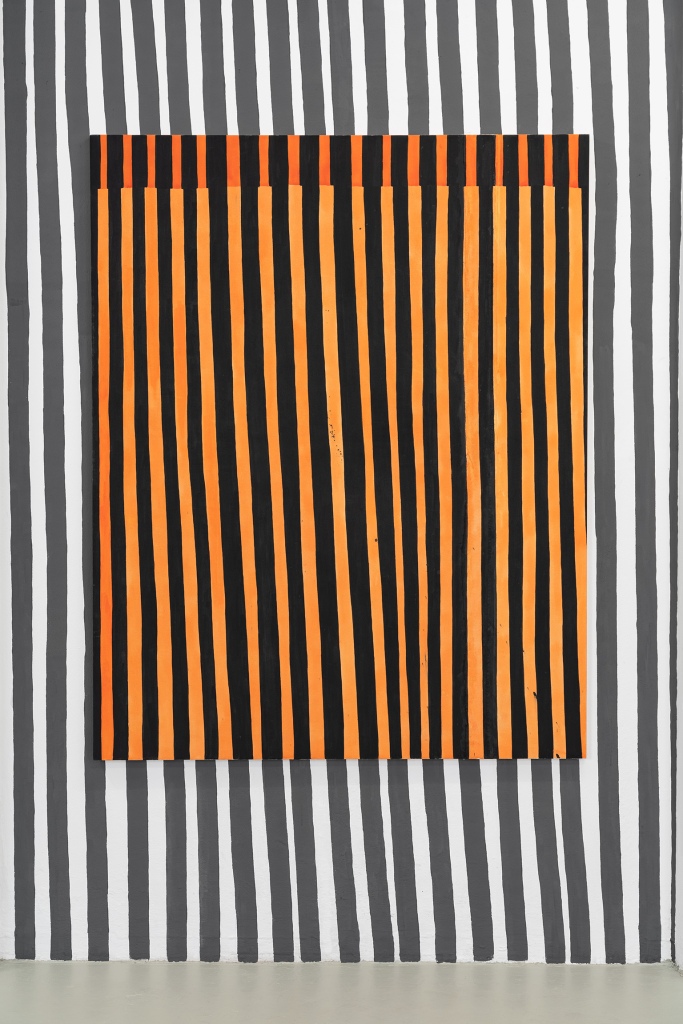

Installation view, “Lotta Bartoschewski / Sophia Domagala — WELTANEIGNUNG”, ad/ad https://www.instagram.com/adadprojectspace/, Hannover, 2021, “Schwarze Streifen auf blau”, acrylic on canvas, 107 x 83 cm, 2021, “Schwarze Streifen auf rosa und rot”, acrylic on canvas, 172 x 138 cm, 2021, “Schwarze Streifen auf rosa und rot” (detail), acrylic on canvas, 172 x 138 cm, 2021, “Schwarze Streifen auf orange”, acrylic on canvas, 136 x 171 cm, 2021, “Artistry of Braves_1” and “Artistry of Braves_2”, pen on newspaper, 14,5 x 20 cm, 2021

Lotta Bartoschewski / Sophia Domagala – WELTANEIGNUNG (World Appropriation)

We have essentially overtaken everything. Everything is “post”—that is, already afterward. Post-internet, post-capitalism, post-modernism. Were we too slow? Are we only able to face a world that we think is spinning faster and faster by becoming faster and faster ourselves? By processing things even more efficiently and rigorously? Only by growing can we survive, cries the unfettered neoliberal market that surrounds us. “If acceleration is the problem, then resonance may be the solution,” proclaims Hartmut Rosa, however, in his book Resonance—A Sociology of our Relationship to the World. He postulates the hypothesis that “an aimless and interminable compulsion to increase […] ultimately leads to a problematic, even pathological relationship to the world […].”[1] For where should we position ourselves once we realize that higher, faster, and further are no longer attractive categories? The artists Lotta Bartoschewski and Sophia Domagala explore Hartmut Rosa’s concept of “world appropriation” in their exhibition of the same name, Weltaneignung. After all, every work of art is always an attempt to situate ourselves in the world and to determine the exact coordinates between which we operate. At the same time, we appropriate the world through art, through the fact that we are producing something, and evade this aforementioned urge for more—because the things that are being produced here are not subject to any market-inherent logic. Lotta Bartoschewski often uses objects that are not only unconstrained by any market-inherent logic, but also those that we would otherwise reject: one-cent coins that we have been collecting forever, only to never get round to taking them to the bank, old newspapers with yesterday’s news.

Here in Hanover, an isosceles triangle seems to float above the ground. It invites visitors to react to it—makes them, even. Because the triangle is placed in the middle of the space, they have to respond to it: Do they walk around it? Do they step over it? This narrative opens up a reciprocal game between body and space. The surfaces of the plaster sculptures, made especially for the space, reveal the negative imprints of the molds, whose interior Bartoschewski painted and lined. The plaster records everything, accurately reproducing all the information fed to it previously. What is then depicted in the plaster is the mirrored trace of human activity. Every fingerprint, every fiber is visible. One-cent coins are gathered on the structure like jewelry; through the images imprinted on the coins, they tell their own stories of the circulation of value and the meanings attributed to them. Another sculpture, a rectangular frame leaning in a recessed alcove, features imprints of newspaper clippings. Their raison d’être is no longer drawn from the news they proclaim, but from the fact that they can be used in a different way. They, too, are only recognizable in their mirrored form due to the printing process. Bartoschewski places them in a different context and gives them a new purpose, one that is no longer linked to usefulness and efficiency.

Sophia Domagala’s striped paintings are positioned differently. They are an endless sequence of repetitions and the same gestures, softened only by small discontinuities. The line is the simplest and most universal form, yet also the greatest and most radical challenge. For no freely painted line will ever be perfect; even the attempt is doomed to fail. They act like a grid through which a window to the world emerges. Something that frames the main action and offers it a stage. The space in between becomes an infinitely expandable resonating body. Domagala contemplates each stripe thoroughly, like a word. While there was sometimes writing in her work in the past, it has given way to stripes here, which now take on the task of corresponding with the viewer. For isn’t writing ultimately stripes and lines strung together? Domagala systematically explores the vertical line in various states: laid over a newspaper clipping, as a wall painting, or on canvas. In each instance they establish new spaces and enter into direct correspondence with the viewer. In each stripe lies a new chance, a new attempt. All are the same yet each one is different.

While Bartoschewski’s work is established in the space and urges action in a playfully inviting gesture, space is revealed in Domagala’s work through repetition.

The works of both artists function here as a resonance space in which we can relate to the world. That is precisely why it is interesting to look at them together. If you wanted to break it down, you could say: Bartoschewski works disruptively, Domagala repetitively. According to Rosa, art “keeps your mind open to the fact […] that another relationship to the world is possible.”[2 ]We thus learn the different ways in which we can appropriate this world, how we can encounter it, and how we can enter into correspondence with it. Without any acceleration, only the ability to immerse ourselves in contemplation. Because when Nas asks, “Whose world is this?”, the only correct answer is one that Rosa would also like: “The world is yours, the world is yours—It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine.”[3]

TEXT / Laura Helena Wurth

[1] See Hartmut Rosa, “Resonanz—Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung” (Suhrkamp Verlag: Berlin, 2016), p.14, [2] Rosa, “Resonanz”, p. 495, [3] See Nas, “The World Is Yours,” by Nasir Jones, Illmatic (Columbia, 1994), LP. / PHOTOGRAPHY / Samuel Henne